07 Dec Citizens Foundation Case File: Your Constitution, The Game

Citizens Foundation America’s Executive Director Josh Lanthier-Welch discusses how he came to pro-democracy, civil society innovation as a calling, through a game about Constitutions.

We thought it would help interested citizens and prospective supporters of our pro-democracy non-profit organization understand what we do a little better if we told the story of one of the projects that got the US side of our operation, Citizens Foundation America, started.

In the long, long ago time of late 2018 — before Covid, before the US Capitol was stormed, an innocent time that seems like a decade ago, but we must all sheepishly admit remains just 3 years past — I found myself, in my hometown of Honolulu, Hawaii, having just sold the small, locavore ice cream business I had spent 10 years building as a brand from nothing, trying to decide what to do next.

Our little family venture had not just been a socially responsible business, we had been truly engaged in the project of trying to make Hawaiian agriculture more sustainable and secure; going to schools to rap with the kids, partnering with farms, lobbying legislators, sitting on panel discussions endlessly, etc.

But despite our best efforts, we watched the economic, logistical, and consumer support situations for Hawaiian Ag worsen every year. A friend of mine counseled me with the cynical wisdom, “the term ‘Socially Responsible Businessman” is an oxymoron; if you want to save the World, go work for a non-profit. If you want to be successful in business, lie, cheat and steal to make a profit.” So, after the sale of the business, I was determined to explore my job options in the “saving the World” sector.

As if by magic timing, that week my phone rings, and it’s my dear chum and former collaborator in multiple projects in the video game industry from 1999-2006, Robert Bjarnason. I had the vaguest idea that he was working on digital democracy on his own distant, isolated, volcanic island; it had not occurred to me that he might represent an avenue into my nascent career in the public sector. Before I had sent out a single CV for philanthropic or NGO work, here was a favorite former comrade, someone who had previously offered me two storied gigs in an earlier career, wandering in, with his own leitmotif, from Stage Left, to give me an opportunity in exactly the sort of work I had just decided to start looking for.

The offer had two components that together would amount to substantial part-time consulting work over the next 18 months. One, the larger, seemingly more important project, was the Populism and Civic Engagement project (PaCE, for short), funded by the EU, and urgent in its impulse, as populism seemed everywhere to be leading to illiberal forms of democracy.

The second, which this case study will examine, was a smaller project originated with the University of Iceland, led by professor Jón Ólafsson, which provided funding and collaboration on the effort: an “edutainment” game idea, designed to help Icelandic students and citizens understand the process of shaping a Constitution, given the fact that they found themselves nearly a decade into the hotly contested struggle to rewrite their document of governmental consecration, following the political turmoil resultant from the 2008 financial collapse.

A game that would offer an engaging fun experience, while still teaching the players a substantial amount about the history and mechanics of writing a functioning constitution, capable of providing the foundation for a working government; I found the project instantly compelling.

As I have mentioned, the PaCE project felt undeniably more like the “saving the World” part of the equation, in the churning pundit panic of early 2019’s commentaries on Brexit, Trump, Orban, Bolsanaro, etc — it seemed like the serious business I had hoped to contribute to. But the chance to make an insightful and fun educational game about writing a constitution with one of my favorite co-conspirators from the gaming industry after a 13 years lapse, had the distinct feeling of “getting the band back together again, man.”

Having worked in mobile gaming with Robert previously, I understood the platform and style of game experience we wanted to provide; one that had simple to learn mechanics; possible mini-game sidebars; a modular game flow, with a sense of beginning, middle, and an end; with a text-driven gameplay necessary to deliver the information and education; while still having a unique visual style and some 3D elements. Our ambitions did not necessarily match our budget, but that had never stopped us before.

My initial thoughts centered around the mythology of Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton here in the US, taught in classrooms and, these days, in song on Broadway. The two men had ideological differences, and struggled against each other, supported by different factions and constituencies among the other “Founding Fathers”, and the conventional wisdom held that this competition for authorship ended up strengthening the final document.

This immediately suggested a basic gameplay — “you be Jefferson, and I’ll be Hamiltion, and — Fight!” Players would represent different perspectives on a constitution’s consecrations of authority and enshrinement of citizens rights and the tensions between the two, and maneuver to advance their agenda through controlling as much of the authorship of the document as possible. It seemed like a natural fit for a trading card style gameplay, and that fit meant designating different concepts of constitutional design as “cards”, or modules of play, would provide such gameplay quite easily.

Despite being an avid student of history and news junkie, I did not have the full chops to teach a Freshman seminar on constitutional design when I started the project; luckily, six months into researching and designing the game, I had done enough of a crash study that I felt prepared to do just that. Immediately in my initial research, I discovered that game theory and the “constitutional process as game” metaphor resided at the core of the field of study. Peter Suber’s seminal game concept Nomic came up repeatedly as a touchstone for understanding constitutional mechanics. To get this right, I realized, I would have to highlight the essential “game-ish-ness” about the very idea of drafting a constitution for a government.

At the time I was working on the design, I also happened to be reading Daniel Kahnman’s Thinking Fast and Slow, and it inspired my thinking on the different modes of play in the flow of the game. There should be slow modes of engagement, while the player studied game assets that had lots of textual information, and faster, “twitch” moments, when they relied on what they had just learned or already knew, as they responded to challenges in the game. I had the insight, novel to me, but possibly old hat to experienced “edutainment” designers, that this combination would produce an optimal educational game experience, with “slow thinking” play modes for learning complex new concepts, and a “fast thinking” mode wherein the player used that new learning in a twitch-play, intuitive manner, which in turn would reinforce retention of that new knowledge.

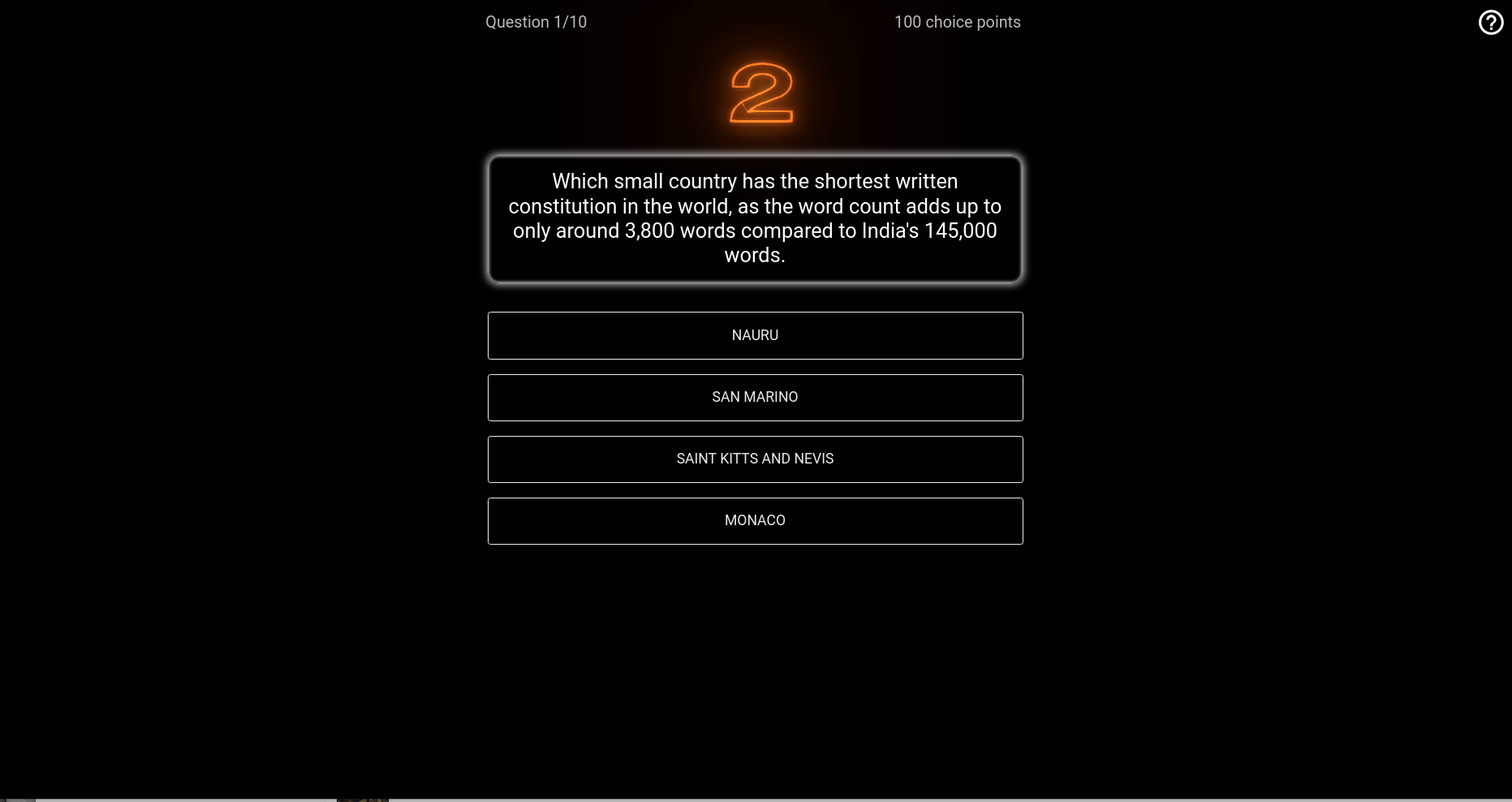

I knew I wanted to start with a quiz show style minigame, to give the player a sense of how much they knew about the theory and history of constitutional design. We would shoot for 80% serious questions — “What’s the oldest parliamentary body in Europe?” — a gimme for the home team, with the answer being Iceland, with their Althingi having been established in 930 AD; and about 20% light hearted fun to set the mood — “What style of Legislative body is the Imperial Senate in Star Wars?” — unicameral, in case you were wondering.

The player’s performance on the initial quiz would determine a number of base points the player begins playing with. We debated calling them “Authorship” points, or “Persuasion” points, and ended up working our way around to the idea that these points represented the player’s political capital in influencing the design of the imaginary constitution the game would simulate. You got 100 base points, and up to 50 additional points for a perfect score on the quiz portion.

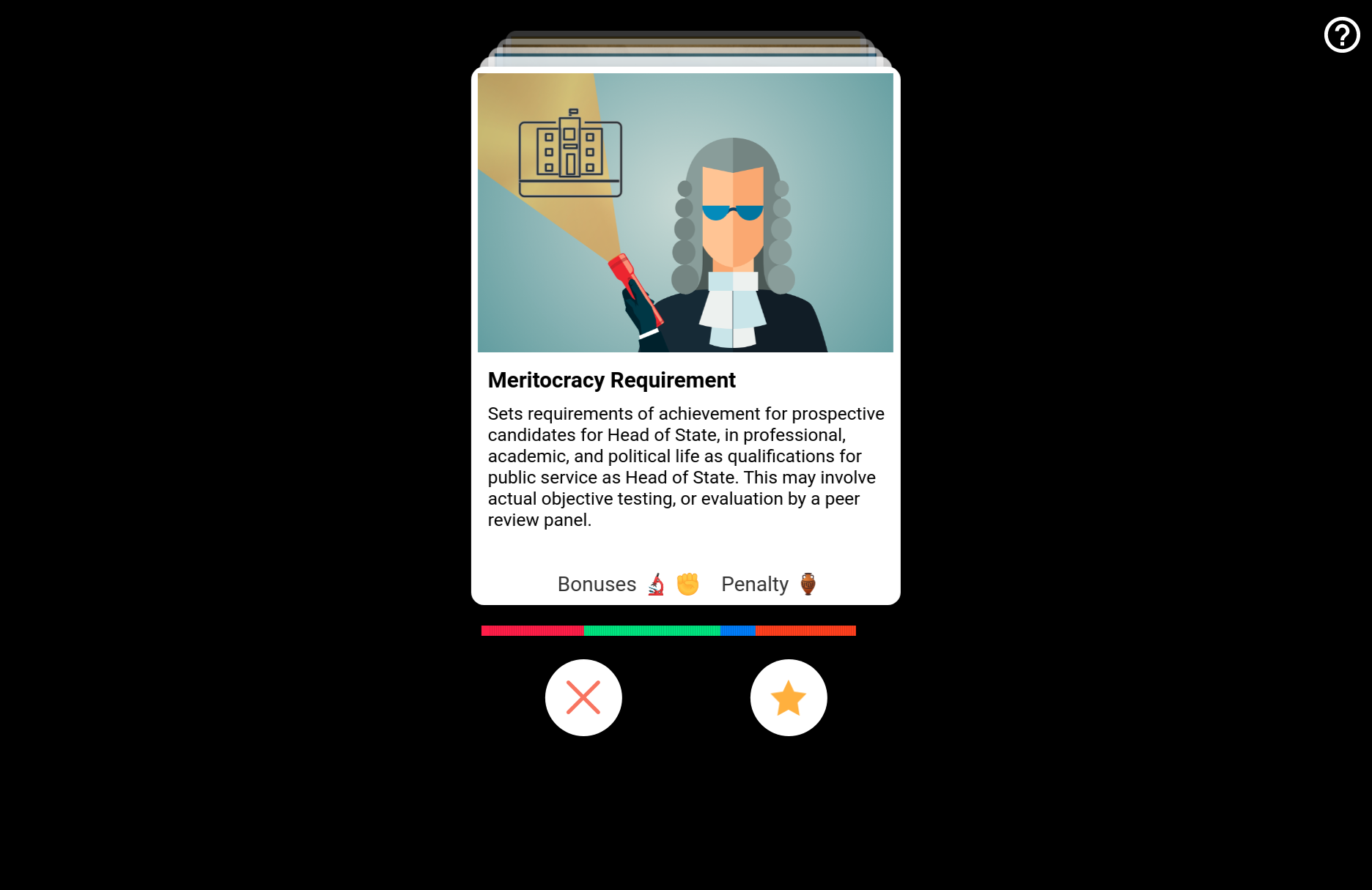

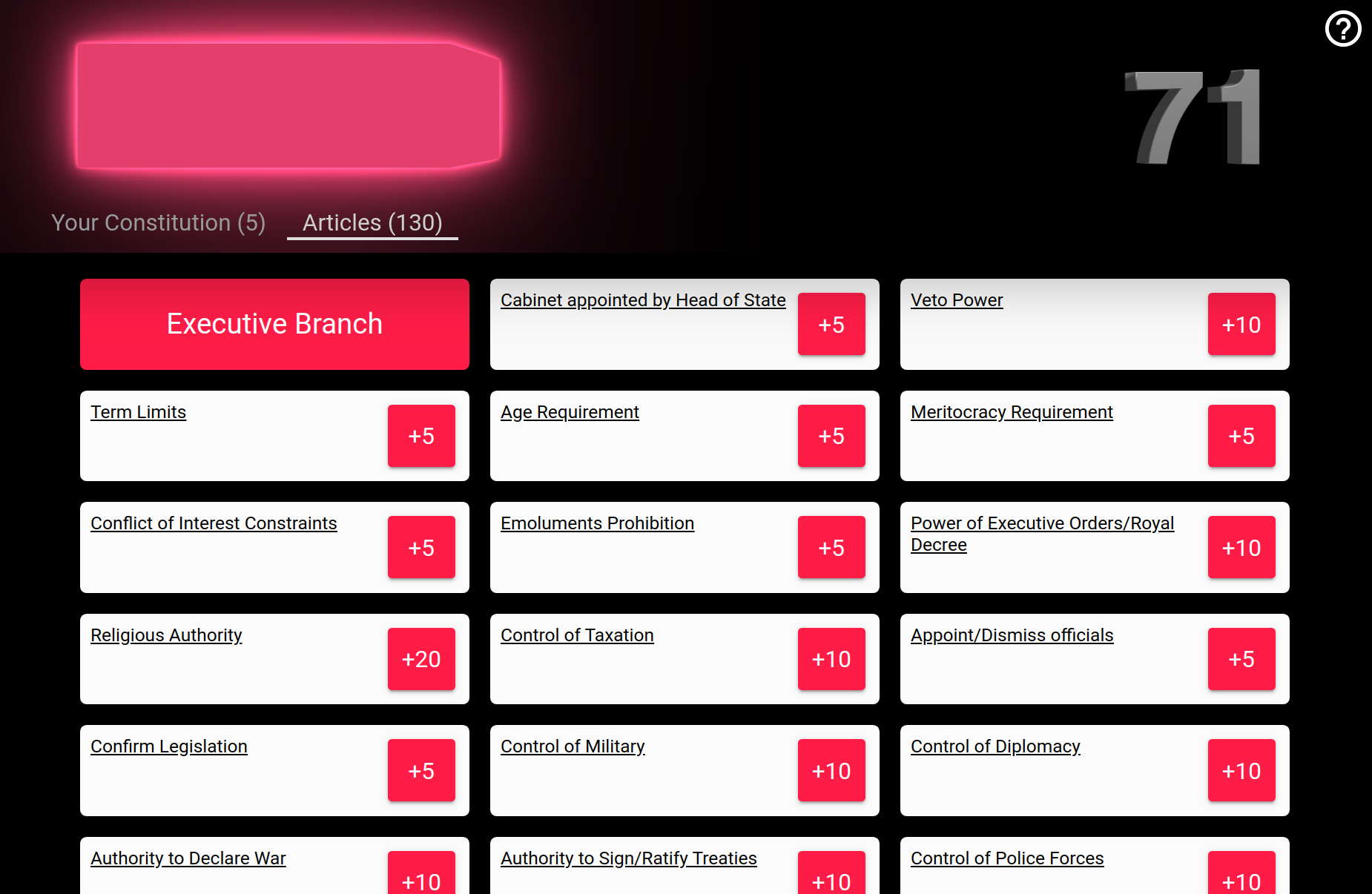

Multiplayer in my original conception relied on following the quiz show with a “deck design” phase, with the player spending some time reviewing the “cards” — modules of play that represented different overarching concepts in constitution design and the history of jurisprudence. These ranged from the simple, like “Habeas Corpus” or “Bicameral Legislature”, to the more experimental, contemporary concepts like “Universal Ownership of Mineral Resources” and the “Right of Dignified Death”. We dutifully set about designing these modules, and the way they would appear to the player in the user interface.

Each “card” concept would rely on a brief bit of snappy prose explaining the concept, provided by me, and what came together as a beautiful, whimsical visual style provided by Citizen Foundation’s creative director, Guðný Maren Valsdóttir. Though they would evolve right up until release, we felt confident early on that we had the right look and feel for these elements.

Around this time we had that experience common to the arc of much professional game design, when the design’s lofty ambitions and feature creep come up against the hard realities of the time and money remaining to execute. It became apparent that we would not be able to bring the multiplayer concept to fruition, and began modifying the game for a “Solitaire” form of play, built on the mechanics we had developed so far.

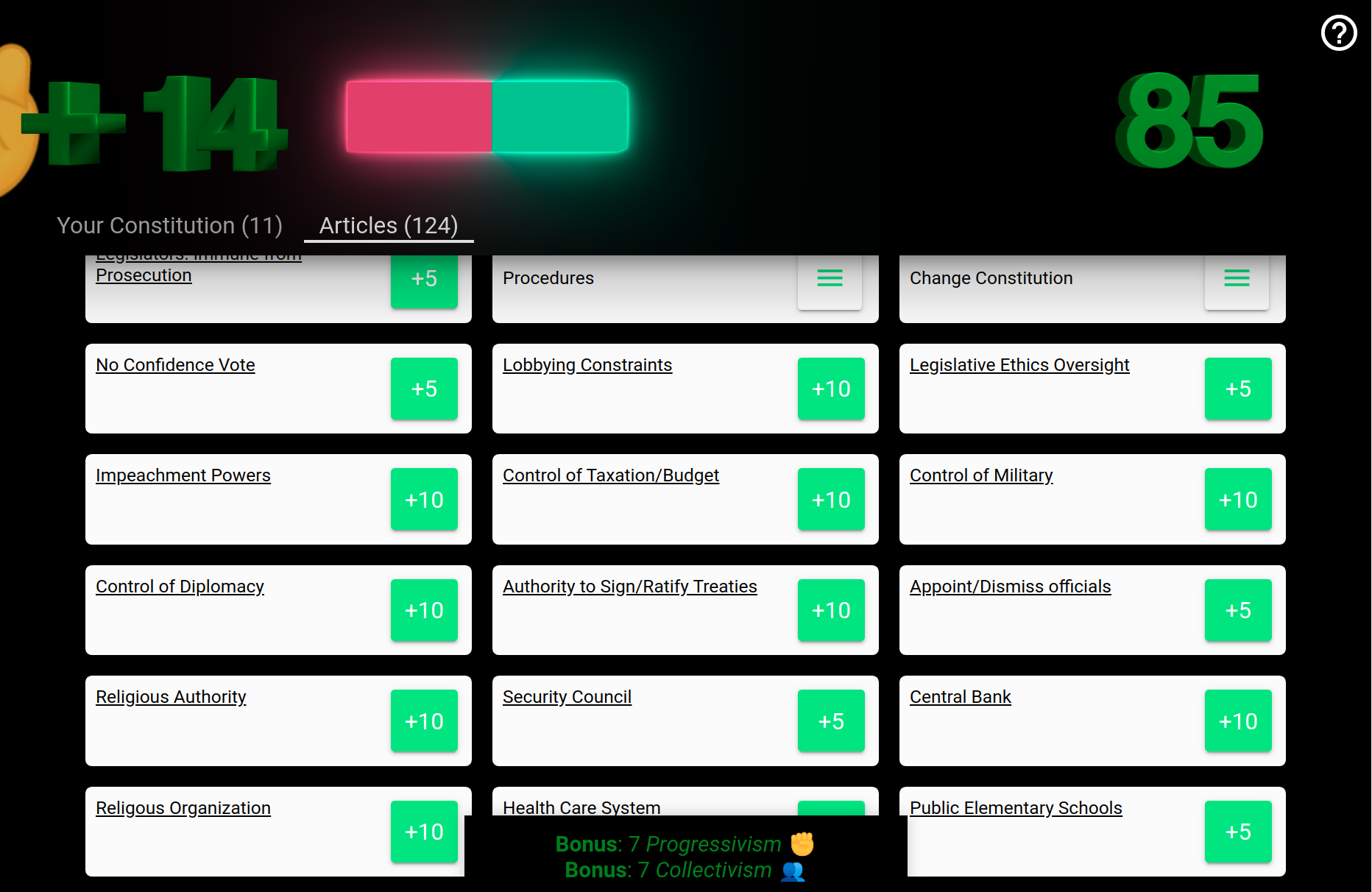

This modification worked easily, because the concept of “political capital points” lent itself to solo play, with the player vying for the approval of constituencies within the society they were trying to govern. As such, we had to come up with a system that evaluated their design choices, and gave bonuses and penalties to the point score based on how “popular” these choices were with the fictional, in-game nation for which they had set out to write a constitution.

Here, we discovered a serendipity with the PaCE project, the two simultaneous projects seemingly, inadvertently related. The analysis of social trends and demographic opinion shifts in the internet’s discourse around Populism required a very similar taxonomic approach to the thought process around designing a “Nation Character Sheet” for Your Constitution’s solitaire play. Like the Hardy Boys realizing they had stumbled across the same mystery their G-man father looked to solve, this synergy between the parallel projects offered a palpable sense of being on the right track.

The character sheet we ended up going with for the game looked like this:

Country’s Cultural Attitude Indices

Authority____ Liberty_____

Science_____ Tradition____

Collectivism__ Independence____

Privacy______ Law/Order____

Social Progress/Egalitarianism___

Country’s Raw Stats

Population___

Geographical Size____

Natural Resource Wealth___

Border Density____

Hostility of Neighboring Countries___

Barriers to Citizenship_____

A fictional nation in the game would have its cultural attitudes mapped across 9 conceptual values, the precise definitions of which we debated and refined, with valuable input from our academic collaborators at the University of Reykjavik. Each one would have a value of 1-10, and this value would determine the effect on the player’s Political Capital Points when they implemented a constitutional design element in the course of play.

Deciding what these values should represent proved the most insightful part of the process. Roughly organized in binary pairs (Authority/Liberty, Science/Tradition, etc), we understood implicitly that a society could have placed a high value on each conceptual index, and a high value on its “opposite” — a culture could highly value scientific research while still having a traditional religious theocracy as a government, namely the modern day example of Iran. We realized these indices were a simple and elegant way of modelling the tensions within a country’s cultural fabric, something that we had been elucidating in the “real” world with the PaCE project.

These Attitude Indices would allow us to assign bonuses and penalties to the different constitutional design concept modules. These point modifiers would be “under the hood” — meaning the player would know what their fictional nation’s Attitude Indices were, but they would not know the direct relationship between that and the point value of the bonus or penalty. This indeterminacy would give the solitaire play some “twitch”, “fast thinking” intuitive play.

We initially toyed with the idea of letting the player quickly design the country they wanted to simulate writing a constitution for. This quickly revealed my roots as an RPG nerd, and I had to remind myself that the audience for this game was from middle school to college freshmen, and as an informational amusement to a wider adult audience, not for a bunch of min-max AD&D geeks at the local library rec room.

Instead, we came up with a list of pre-set, pseudo-fictional nations, meant to represent past and current constitutional creation scenarios. Here we felt we had struck on something meaningful in teaching the history around this topic. How different was 1783 in Philadelphia, from 1849 in Copenhagen? Or 1979 in Tehran? These questions could give the players insights into constitutional design history in a vivid way through gameplay. We settled on a list of 9 options:

- Happy Arctic Island Nation Now (Iceland)

- Nordic Peninsular Kingdom 1849 (Denmark’s June 5)

- 13 Colonies 1783 (US Constitutional Convention)

- ‘Murica Now (US currently)

- Islamic Revolutionary Republic 1979 (Iran at fall of Shah)

- Jolly Island Kingdom Now (Brexit Era UK – time to codify a constitution?)

- Pseudo-Communist Asian Superpower Now (Mainland China fantasy of democracy)

- Future Land (Imaginary Utopian State)

- Splinter State (Imaginary Anarchist State)

After reviewing their priorities for constitution design, and selecting their simulated national identity, the player was ready to play the solitaire version of Your Constitution, in its Alpha form.

Here, Robert’s brilliance for simple 3D design solutions came in, and we developed a user interface for the solitaire play that presented a slot machine/pachinko/pinball sort of feel, that dramatized the bonuses and penalties in a simple, engaging way.

Now we had a game that was ready to present to our first classroom of playtesters — a group of grad students and a handful of professors from the University of Reykjavik. Initial reviews were mixed, but generally positive, and with the help of their input, we tweaked and streamlined the play, and created an automatic “outcome generator” — basically a response from the game based on the player’s performance with regard to each of their country’s Cultural Attitude Indices, with enough content that you would need to play the game multiple times to see repeated material.

After some fine tuning of bonuses and penalties, based on feedback from people who actually had degrees in Political Science and Constitutional Law, we had a game that we could share with the intended wider audience, promoted as part of the lead up to the referendum vote in Iceland. It also got some traction in classrooms around Europe, in places as far flung as Barcelona, Spain and St.Petersburg, Russia. It was a quick and informative 20-30 minute solo play time, garnered some positive feedback and public goodwill from the Icelandic community and press.

At that point, our attention turned to the Smarter New Jersey project, one of our first civic participation efforts in the United States, led by GovLab. The project provided a forum for improvement and innovation to all 120,000+ State employees in the Garden State. This project prompted the founding of Citizens Foundation America, as it showcased the effectiveness of the engagement platform Citizens Foundation Iceland had been developing for the preceding 11 years, Your Priorities, successfully used in dozens of countries all over the world. This inspired us to imagine extending this public online space concept across the US, providing places for people to interact free from private sector drivers like data mining and ads, that foster productive debate and participation without toxic trolling and polarizing click-bait.

We also had another year of work ahead of us training and analyzing AI to monitor political speech online, the culmination of which you can visit at the PaCE Dashboard site, here: https://pace-dashboard.citizens.is/

We still wistfully hope that the funding will one day materialize to allow us to return to the design of Your Constitution, and give it the Jefferson vs. Hamilton game play we had originally conceived. In general, designing the game had given insights into an ideal simulation of how a culture’s values could influence and shape the core tenets and constitutional rules that formed the foundation of the institutions that they allowed themselves to be governed by. The PaCE Project analysis allowed us to look at how the world’s politics really were, while Your Constitution gave us insight into how those politics could be, if the feedback loops between those that drafted the laws, and those who had to live under those laws, had the instantaneous transparency and efficacy they required for people to feel heard, and their concerns answered.

Play Make Your Constitution: https://demo-make-your-constitution.yrpri.org/

Check out the Open Active Policy platform, the open-source game engine behind Make Your Constitution: https://github.com/CitizensFoundation/open-active-policy

To get started with the open-source Your Priorities citizen engagement platform click here: http://www.citizens.is/getting-started/

Make Your Constitution is a part of “Democratic Constitution Design” (DCD), a project of excellence funded by the Icelandic Research fund, and hosted by the University of Iceland.

The PaCE Dashboard has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 822337. Any dissemination of results here presented reflects only the consortium’s view. The Agency is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains.